One of the joys of being a poster dealer it that you never know what’s going to turn up next. Hours spent scouring auctions or following up leads might result in one or two ‘new’ posters to add to the list, or a small collection of miscellaneous material. Such random discoveries rarely provide a coherent insight into the past, however striking an individual poster might be. Occasionally, though, a forgotten hoard of vintage posters comes to light which collectively reveal something about the aspirations and design values of the society that produced them.

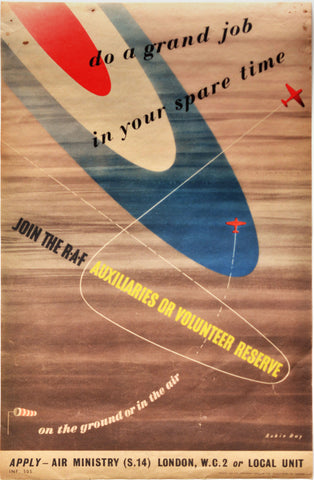

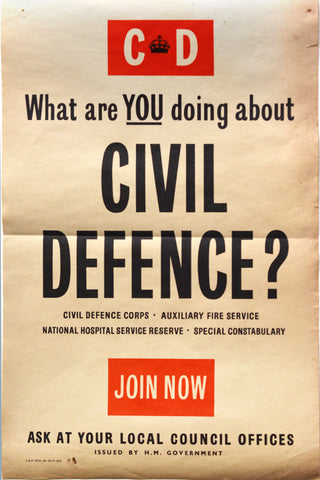

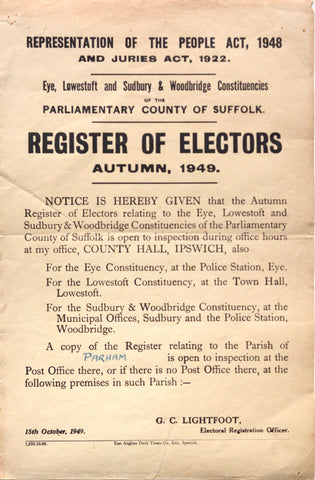

This is exactly what happened a few weeks back, when I was lucky to find fifty ‘counter-display’ posters rescued from a long-closed Post Office in Parham, Suffolk. What makes this group so interesting is that all the posters date to just three years, 1949-1951, thereby offering a fascinating snapshot in time. Why they were saved is a mystery, although it’s clear from the corner pin holes that each had been dutifully displayed, making their survival all the more remarkable. Not surprisingly, most were published by the General Post Office (GPO) to promote services or convey information. The rest were printed by various government agencies on topics as diverse as Civil Defence, local elections and the prohibition of sending money abroad. Among these official notices are calls to join the army and Royal Air Force, together with more prosaic reminders to hand in out-of-date National Insurance cards and buy National Savings Certificates. All of which serves as a reminder of the Post Office’s role in disseminating official information at a local level, as well as the preoccupations of a post-war nation entering a new era of Cold War preparedness.

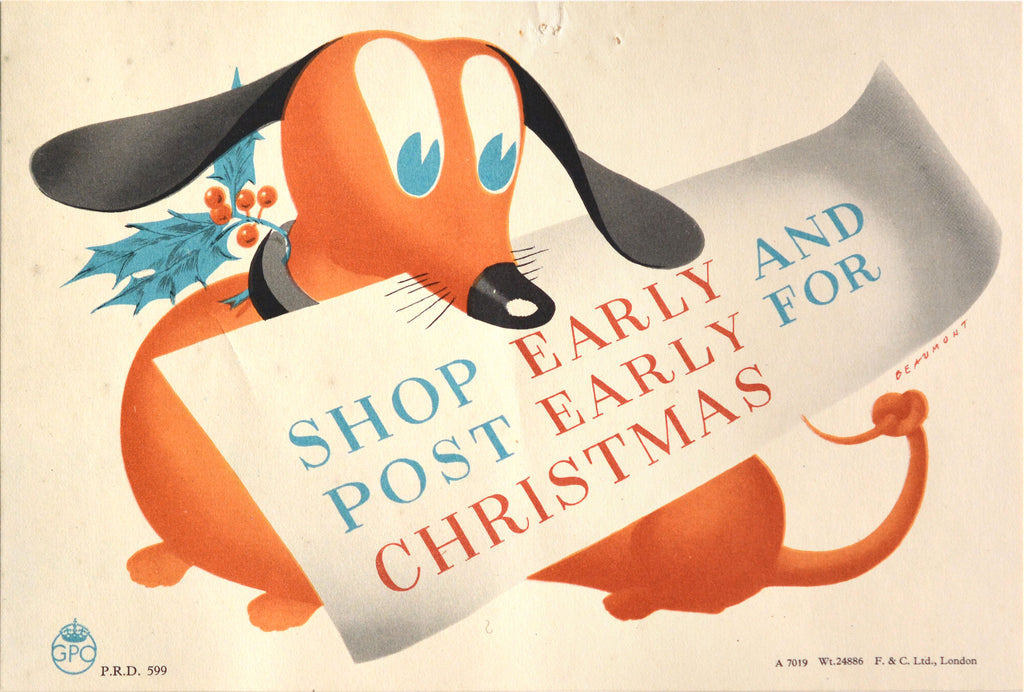

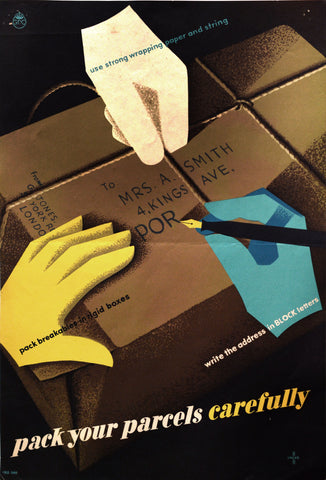

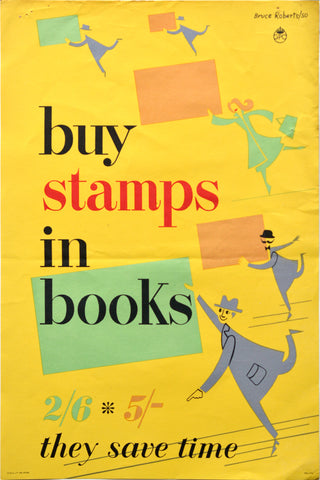

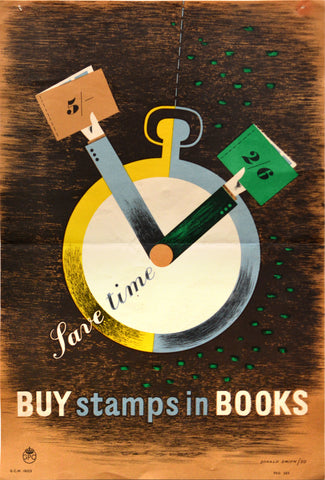

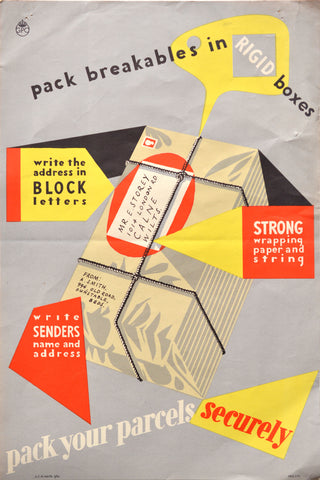

But it is the GPO posters that really stand out. Their bright, modernist-inspired, designs are in stark contrast to the often-dour government notices and offer an altogether more optimistic narrative about the present which anticipates the celebratory tone of the Festival of Britain (1951). This was no accident, as since at least the 1930s the socially progressive GPO had been at the forefront of graphic design innovation in Britain, seeking ever clearer ways to communicate with its customers.

Yet, as the design historian Susannah Walker has pointed out, relatively little attention has been given to the public reception of GPO posters which adorned every local post office from Lands End to John O’Groats. Compare this with the huge amount that’s been written about London Underground or Shell-Mex publicity (both pioneers of effective poster advertising), which would have been seen by far fewer people at the time – certainly outside of London and the big cities. Even railway posters were mainly restricted to station hoardings, whereas the daily transactions of everyday life meant that a significant proportion of the population would have come into regular contact with the designs of the GPO. What customers thought of the posters is, of course, another matter, but the GPO’s nationwide reach exposed the public to new ideas in graphic communication like no other organisation at the time, thereby helping to spread a distinctive post-war visual aesthetic.

The posters discovered from Parham are a case in point. In 1950 the post office there was run by Roy and Janet Frost. It served a small rural community close to the Suffolk coast, and far away from the bustling metropolis of London with its new fashions and ideas. Yet both were linked by the breezy graphics of the GPO, suggesting a shared national endeavour and a connectedness with the outside world. I’m grateful to the Parham Facebook Group for sending me a lovely photograph of the Post Office from this period, showing workers and villagers going about their business. Its intriguing to think that they almost certainly saw some of the posters reproduced here.

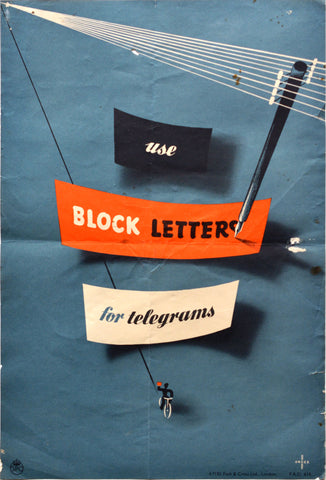

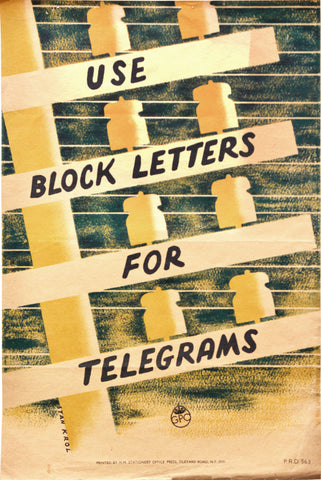

So, who were these posters by and what was the GPO trying to achieve? By far the best account of the Post Office’s poster campaign comes from Paul Rennie, and I’d strongly recommend anyone interested in the subject to get hold of a copy of his book. But in brief, Paul has shown how the national importance of the postal service enabled the GPO to commission new designs in the face of severe post-war shortages (e.g. of machinery, ink and paper). This in turn created a thriving, and relatively stable, environment for a new generation of poster designers who may have struggled to find work elsewhere. As an indication of the changing times, London Transport had moved from commissioning over 100 posters a year in the 1930s, to about 50 by 1950 (a figure that was to drop even further before the decade was out). In comparison, the GPO commissioned around 60 posters in 1950 from almost 30 different artists. A significant number of these were emigres who had previously come to Britain to escape Nazi tyranny, including FHK Henrion, Manfred Reiss, Dorrit Dekk, Stan Kroll, Arnold Rothholz, Hans Schleger, Hans Unger and the design duo Jan Le Witt and George Him (Lewitt-Him). Home grown talent included Tom Eckersley, John Rowland Barker (‘Kraber’) and Bruce Roberts among many others who were to make their name during the 1950s. Although different stylistically, all these designers shared a modern aesthetic inspired by pre-war continental developments in graphic communication.

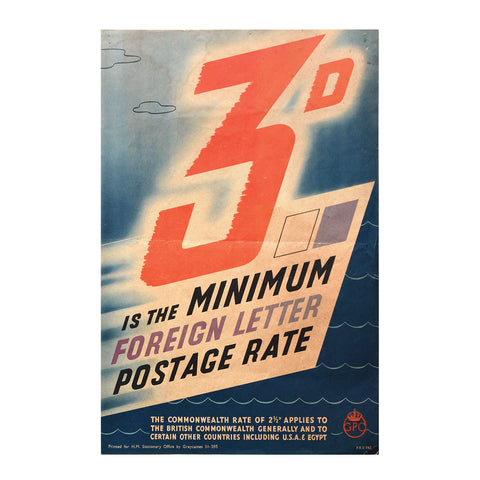

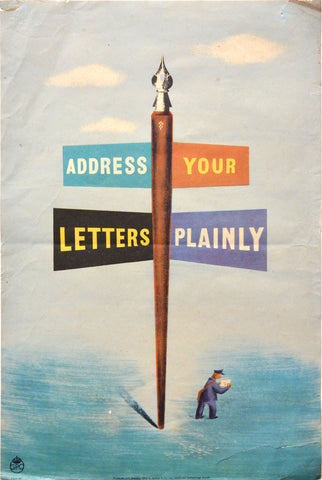

The subject matter for the posters discovered at Parham, though, is unlike much of the GPO’s pre-war output. Then the Post Office had employed high profile artist-designers to create large format educational posters, often depicting the history or reach of the GPO, for distribution to schools and display at larger post offices and on transport vehicles. Instead, the small format post war posters are entirely focussed on conveying practical information clearly and concisely and were designed to be pinned on counter displays and post office walls.

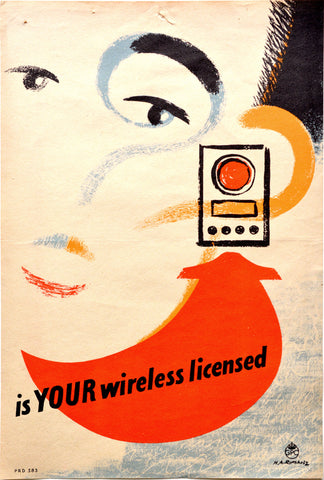

From the surviving sample, it would seem that the GPO was especially keen to persuade the public to package and address mail correctly, as well as using the Post Office to buy stamps, telegrams and related publications. Yet all of this is done with a light-hearted airiness, rather than stern warnings or brusque messages. Even reminders to renew wireless licences are wittily expressed.

The surviving sample is not complete. At least 120 GPO posters were printed between 1949-51, to say nothing of the miscellaneous government notices that were displayed alongside. Its also likely that many more Post Office Savings Bank posters were produced during this period than are seen in this sample, although surviving information is patchy. The fifty surviving posters from Parham, though, provide a rare opportunity to understand how posters were displayed together and to be reminded of the breadth and quality of the GPO’s output over just three years.

All the posters included in this blog post were originally offered for sale. Please click on an individual image for current availability or view a selection available for sale here. My thanks, as ever, to Susannah Walker of Quad Royal blogging fame for her insights, and also to the Parham Facebook Group for generously supplying additional info. If you’d like to find out more about the history of the GPO’s poster campaigns, visit Post Office Museum.

Comments on post (0)

Leave a comment