Last year London Transport Museum asked me to co-curate Poster Girls, a new exhibition looking at the remarkable, and neglected, role of women poster designers in selling the Capital's transport system over the last 110 years. The show, which has garnered much critical acclaim (largely thanks to the outstanding work on show and the quality of LTM's design) runs until early 2019.

Since January, I have written monthly 'mini-blogs' for the museum about some of the featured artists.

Here are the first four, originally published on the LTM website.

Nancy Smith, 1922

Nancy Smith, 1922

A Room of One’s Own

The first women poster pioneers

90 years ago, the author Virginia Woolf argued that “a woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction”. This call for a literal and figurative space, free of male control and domestic responsibilities, applied equally to all areas of female creative endeavour. Yet as Woolf knew all too well, women had few opportunities for genuine financial and creative independence in the 1920s. Commercial art, as graphic design was then known, provided one of these opportunities, and London Transport was at the forefront of commissioning female talent. How did this come about?

Miss Bowden, 1917

When Frank Pick took charge of the Underground’s publicity in 1908 the male-dominated advertising industry regarded women artists, at best, as suitable for illustrating ‘feminine’ subjects or children’s book. From the start, Pick took a progressive view towards commissioning irrespective of gender or subject matter. The first poster by a woman appeared on the company’s trams in 1910, and by 1930 over 25% of all Underground publicity was designed by women. No other British company or government agency took such an enlightened stance or promoted female designers to the same extent.

Vera Willoughby, 1928

In finding young artists Pick was greatly helped by a revolution in the teaching of art and design in London, led by the Central School of Arts & Crafts. Women made up a disproportionate number of the students on commercial art courses, and in Pick they found a willing patron able to jump start their careers with the gift of well-paid and high-profile poster commissions.

Dora Batty, 1932

But it wasn’t a feminist triumph in the modern sense. Male designers were still paid more and achieved greater fame than their female colleagues. And many promising careers were cut short by marriage and the expectations of childcare and running the family home. The names of these female poster pioneers, too, have been criminally neglected by history. Who now has heard of Nancy Smith, Dora Batty, Herry Perry, Margaret Calkin James, or the dozens of successful women designers whose work enlivened the hoardings in the first 50 years of the twentieth century?

Happy 80th birthday to Carol Barker, illustrator and author

The multi award-winning illustrator and author Carol Mintum Barker turns 80 on 16th February. I first met Carol last year while researching LTM’s Poster Girls exhibition, and I’m not surprised to learn that this sprightly artist is celebrating her landmark birthday teaching young women art and design in Rajasthan, India. In fact, Carol has been visiting and working in India since the 1970s, and has helped many women out of poverty and on to university through art education.

Carol Barker, 1969

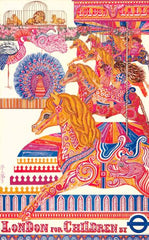

Her remarkable career began sixty years ago. Inspired by her artist father, John Rowland Barker, Carol attended Bournemouth College of Art, Chelsea Polytechnic and the Central School of Arts & Crafts. She became a freelance illustrator in 1958, eventually contributing to over 30 books. Until the late-1970s, her work was most closely associated with children’s book illustration, including a collaboration with the comedian Spike Milligan (The Bald Twit Lion, 1968). It was during this period that she designed four posters for L.T. promoting Fenton House (1966), London Museum (1969), Children’s London (1973) and London’s Museums (1979) – a selection of which can be seen in the current exhibition at Covent Garden. Her designs in pen and ink, watercolour, collage and wax, capture the joyful exuberance of the age, and are arguably among the best posters commissioned by L.T. at that time. London Museum, in particularly, is a rich visual scrapbook of the Capital’s past, and visitors to Poster Girls are encouraged to compare the original 3D artwork with the printed poster (both on display). My favourite, though, is the Children’s London pair poster, which was praised by Modern Publicity (1974) as one of the best British posters of the previous year.

Carol Barker, 1973

Since 1977, Carol has undertaken several extensive research trips to India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, West Africa, Tibet and elsewhere to produce non-fiction ‘picture-information’ books for children which sympathetically record day-to-day life in other cultures. On one of these trips she was given a rare private audience with His Holiness the Dalai Lama. Her work, often at the behest of international organisations such as Oxfam and the United Nations, has garnered critical acclaim and achieved worldwide publication.

The bright young things who put women centre stage

Anna and Doris Zinkeisen

Of all the designers featured in Poster Girls, none were as glamourous as the Scottish-born Zinkeisen sisters whose precocious talent, beauty, and modernity propelled them into the centre of interwar London’s fashionable art scene. Typically described in the pages of society papers as ‘extremely pretty’ and ‘brilliantly clever’, it would be easy to view the sisters as the epitome of the entitled ‘bright young things’ parodied by Evelyn Waugh in Vile Bodies (1930). But there was so much more to Anna and Doris than this, as their extraordinary body of work testifies. And as the posters in LTM’s exhibition show, it was a body of work that put confident, independent, women firmly on the centre stage.

Anna Zinkeisen, 1934

Born in 1898, Doris was the elder of the two by three years. Despite the age gap, they trained together at the Royal Academy Schools and by the mid-1920s were sharing a studio in London. The range of their work was dazzling, including book illustration, publicity for railway companies, murals for the Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth ocean liners, and society portraits of the fashionable ‘set’. Doris also developed a hugely successful career as a stage and costume designer for theatre and films, working alongside Noel Coward, Charles B Cochran and Cole Porter.

Anna Zinkeisen, 1934

But it is their depiction of women that strikes the viewer as truly modern. Take, for example, the panel posters produced by Anna for the inside of Tube carriages. These show dynamic, active, women who are not defined by their relationship to men – a far cry from most commercial art of the time. Similarly, Doris’ unpublished poster of female theatre goers (1939) depicts a group of young women enjoying a night out without an obvious male chaperon. And the subject matter, too, is far removed from traditional ‘feminine’ commissions. Anna’s output for the Underground included motor shows, air displays and military parades. There was also something distinctly racy about their portrayal of the modern woman. The scantily clad revellers of Anna’s Merry-go-round poster (1935, lead image above) would raise eyebrows even today, while Doris’ costumes for the West End play Nymph Errant (1933) were regarded as so revealing that the chorus girls refused to wear them. In the changed circumstance of the Second World War, their work became less frivolous but no less assertive, as their moving depictions of female war workers demonstrates.

Doris Zinkeisen, 1939

‘C&RE’

A modern couple who bought a new aesthetic to 1930s poster art

Unique among the artists featured in Poster Girls, Clifford and Rosemary Ellis were a husband and wife design partnership. They married in 1931 after meeting at the Regents Street Polytechnic, and henceforth virtually all their commercial work was jointly signed, often with the initials ‘C&RE’. At the time, this was an unusual demonstration of artistic and marital equality, underlined by the occasional use of the signature ‘Rosemary and Clifford Ellis’ (rather than ‘Clifford & Rosemary’) which can be seen on one of the London Transport posters in the exhibition. In describing their collaborative approach, Rosemary explained that either one might have the original idea for a design which they would then finalise together.

Clifford & Rosemary Ellis, 1934

Whatever the origins of their ideas may have been, the results were extraordinary. Their unmistakable style was characterised by a lively use of colour and form, creating unusual and memorable poster designs. Travels in Time (1937), for example, is almost surrealist in its depiction of a disembodied Charles I against an imagined landscape. Luckily for Londoners, this bewildering image was paired with an explanatory poster (also designed by Clifford and Rosemary) promoting the Capital’s museums. In contrast, their representation of animals and birds, seen in their designs for Green Line Coaches (1933), was wonderfully naturalistic and alive with movement.

Clifford & Rosemary Ellis, 1937

By the late thirties, the couple were much in demand, having designed posters for London Transport, the Empire Marketing Board, the Post Office and Shell-Mex. Their joint output included book jackets, lithographs, murals, mosaics and wallpaper. Clifford was also the headmaster of the Bath Academy of Art and instrumental in re-establishing it as one of Britain’s foremost art colleges at Corsham Court after the Second World War. During the war, Rosemary and Clifford worked together on the monumental Recording Britain project, but are perhaps best remembered today for the 60+ dust jackets they designed for the long running New Naturalist book series.

Rosemary & Clifford Ellis, 1935

The couple’s extensive personal archive was auctioned in 2017 following the death of their only child, the sculptor Penelope Ellis. LTM acquired two rare ‘proof’ versions of ‘Museums’ (1937), showing annotations made by the artists before final printing. These included the replacement of the printed London Transport logo with a hand drawn alternative, which was accepted for the final design.

Comments on post (0)

Leave a comment